Dreaded Passive Losses

A passive loss from a real estate activity occurs when your rental property’s expenses exceeds its income. The undesirable consequence of passive losses is that a taxpayer is only allowed to claim a certain amount of losses on their tax return each year.

A passive loss from a real estate activity occurs when your rental property’s expenses exceeds its income. The undesirable consequence of passive losses is that a taxpayer is only allowed to claim a certain amount of losses on their tax return each year.

When income is below $100,000, a taxpayer can deduct up to $25,000 of passive losses. As income increases above $100,000, the $25,000 passive loss limitation decreases or “phases out.” The phase out is $0.50 for every $1 increase in income. Once income increases above $150,000, taxpayers are completely phased out of deducting passive losses.

Rentals are passive, unless they aren’t

The general rule is that all rental activities are, by definition, passive. However, the Internal Revenue Code created an exception for certain professionals in the real estate business.

Who is a real estate professional?

As discussed in a previous post, for income tax purposes, the real estate professional designation means you spend a certain amount of time in real estate activities.

According to the IRS, real estate professionals are individuals who meet both of these conditions:

1) More than 50% of their personal services during the tax year are performed in real property trades or businesses in which they materially participate and

2) they spend more than 750 hours of service during the year in real property trades or businesses in which they materially participate.

Any real property development, redevelopment, construction, reconstruction, acquisition, conversion, rental, operations, management, leasing, or brokerage trade or business qualifies as real property trade or business.

Can I qualify as a real estate professional?

I get these questions quite often from taxpayers: Do I qualify as a real estate professional? If not, how can I qualify?

There have been many cases that appear in front of the Tax Court where a taxpayer argues they qualify as a real estate professional and the IRS has disallowed treatment and subjects the taxpayer to the passive activity loss rules of Code Sec. 469.

A recent case held that a mortgage broker was not a real estate professional (Hickam, T.C. Summ. 2017-66). The taxpayer was a broker of real estate mortgages and loans secured by a real estate. Although the taxpayer held a real estate license, he did not develop, redevelop, construct, reconstruct, operate, or rent real estate in his mortgage brokerage operation.

The taxpayer argued that his mortgage brokerage services and loan origination services should be included for purposes of satisfying the real estate professional test. The Court held that the taxpayer’s mortgage brokerage services and loan origination services did not constitute real property trades or businesses under Code Sec. 469(c)(7)(c).

We’ve got your back

If you invest in real estate, it can be difficult to keep track of tax laws and how they impact you. At KRS CPAs, we stay on top of all the laws – especially the changes under the new tax reform – and can help you avoid tax problems. Contact me at sfilip@krscpas.com or 201.655.7411 for a complimentary initial consultation.

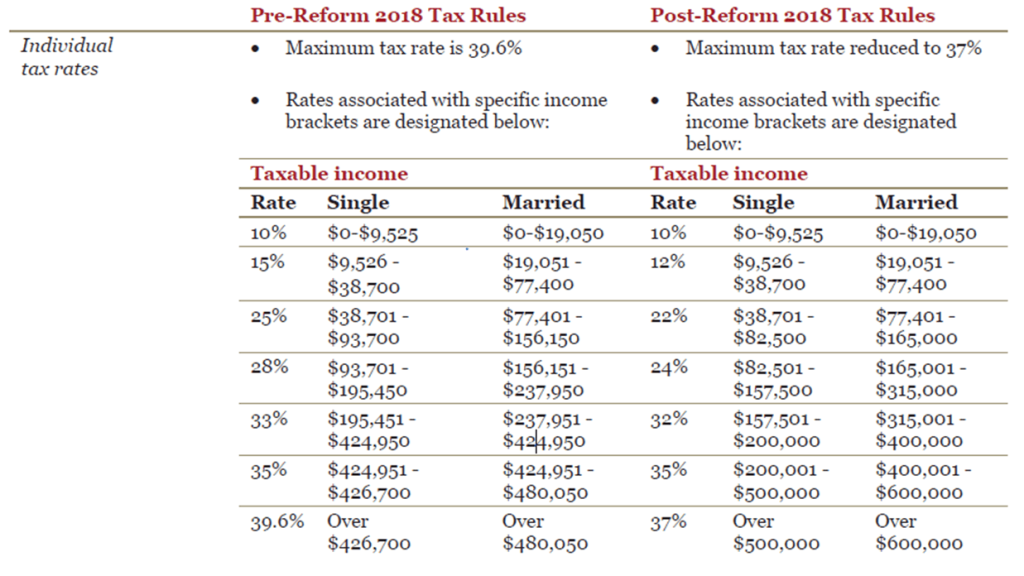

The new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act amends the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) to reduce tax rates and modify policies, credits, and deductions for individuals and businesses. It is the most sweeping update to the U.S. tax code in more than 30 years, and from what we’re seeing, it impacts everyone’s tax situation a bit differently.

The new Tax Cuts and Jobs Act amends the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) to reduce tax rates and modify policies, credits, and deductions for individuals and businesses. It is the most sweeping update to the U.S. tax code in more than 30 years, and from what we’re seeing, it impacts everyone’s tax situation a bit differently.

One of the most valuable assets a taxpayer will ever sell is their personal residence. Under

One of the most valuable assets a taxpayer will ever sell is their personal residence. Under